A few days ago, Gary Herselman died in his sleep. Most of you - especially Notations readers who are not South African - will not know this songwriter and musician whose blistering guitar solos with his three-piece, The Kêrels, and life of excess earned him a comparison with Keith Richards locally. But, read on, and you will get a feel for why so many people who encountered him when he worked at Johannesburg’s iconic Hillbrow Records in the 80s, or in his different musical incarnations, found him unforgettable and are sharing their recollections and tributes on social media.

I wrote about this one-of-a-kind human and artist for the South African edition of Rolling Stone in early 2014. We were probably the only music magazine that would carry a substantial feature on an artist like Herselman who was never close to being a commercial success and who frequently imagined himself to be a dog (you can read an excellent analysis by Warrick Swinney - a contemporary of Herselman’s - here). Writing the story more than a decade ago took me all the way back to 1989, a time when the self-described “alternative Afrikaans” music movement was protesting and pushing back - with sometimes poignant, often confrontational, always emotional tunes - against the apartheid regime’s last throes.

No Direction Home

The first time I saw Gary Herselman, he was going under the name Piet Pers and was thrashing the bass on a wild night that some old-timers at Durban’s Central Methodist Church probably still talk about over cups of tea.

It was 1989, and a motley audience of lefties (and a sprinkling of curious but ultimately unlucky churchgoers) gathered in the church hall, upstairs on Aliwal Street, to welcome the Voëlvry Tour to Natal. As we filtered into the space, we could scarcely believe it had actually made it to our city after reports of a countrywide trek littered with bannings and unmitigated rock’n’roll excess.

In fact, Herselman had already become known to us as the leader of Die Kêrels, whose song “Slang” (off the album Ek Sê, and also featured on the Voëlvry album that we adored) had come to signify, in our minds at least, the omnipresent menace of the Security Branch and the far-reaching tentacles of apartheid’s stealthy iron grip.

But on that night, Herselman was on stage as a member of Johannes Kerkorrel’s Gereformeerde Blues Band (GBB), the main act for many in a line-up that included André Letoit (Koos Kombuis) and Bernoldus Niemand (James Phillips).

I wore, quite unbelievably to me now, a black lace vintage dress and ’50s-style heeled shoes with a front tip so sharp I could have used it to defend myself had the police arrived, as you always knew they could during the 1980s. We later found out, through Pat Hopkins’ meticulously researched Voëlvry: The Movement That Rocked South Africa, that the hall had been booked by “Dirkie Uys” – and that the hapless church official who took it had thought the event was some kind of “youth improvement group”.

Those of us in the audience – which Hopkins describes as “600 of Durban’s flamboyantly dressed, outer-edge rockers” – had no such misapprehensions. In a city ringed by ongoing battles between Inkatha and the UDF and deep in the grip of the security cops based just down the road in Stanger Street, we were there for the music and the message: the lilting sorrow of Johannes Kerkorrel’s Gereformeerde Blues Band’s “Hillbrow”; Bernoldus Niemand’s tragically funny “Snor City”; André Letoit’s sparse, moving “Boer in Beton”.

It seems strange looking back now, but at the time we didn’t even think much about the ability of a bunch of outlaw musicians to get white, English-speaking Durbanites – the kind who laughed easily at shoeless Afrikaans kids on their way to school – to sing in a language we professed to despise. We just knew that, on that night, we truly joined a movement that was deploying music to get a generation to slip the patriarchal shackles of apartheid and dance towards the future. Twenty-five years after that night, long after the context that gave the songs such power had been stripped away, the music that defined Voëlvry still holds up, mostly because of the strength of the songwriting on the 12-track album that bore the movement’s name. And it’s as a songwriter that I again encounter Herselman late in 2013.

It’s a glorious summer’s afternoon when we meet at Lucky Bean in Melville to talk about Die Lemme’s Rigtingbefok – Herselman’s 18-track, independently-released “solo” album that sees 40 musicians and nine producers tackling 16 of Herselman’s original compositions and two cover versions (“Liefde“, from Die Gereformeerde Blues Band’s Eet Kreef – performed by surviving members Herselman, Willem Möller and Jannie van Tonder, with guest vocalist Arno Carstens – and the Radio Rats’ late ’70s hit, “ZX Dan”).

But we start off nostalgically because I want to know if Herselman has as much a sense of himself as a figure in South African music history as we do. Not just because of Die Kêrels and Gereformeerde Blues Band (and even the under-appreciated country-slinger, Archie Pelago), but also because of Tic Tic Bang, one of the first independent music distributors in the country.

Herselman shrugs. “I just did what seemed to be a good idea at the time with everything. Even with the Tic Tic Bang thing. I was just amazed that no-one had put out Jennifer Ferguson and it went from there – Henry Ate, Urban Creep, Van der Want and Letcher.”

Why, then, do you think that so many artists (Albert Frost, Chris Letcher, Arno Carstens, Francois Van Coke, Paul Riekert, Kathy Raven, Valiant Swart, Sannie Fox and Rolling Stone‘s Willim Welsyn among them) and a line-up of producers – Letcher, Willem Möller, Ampie Omo, Colin Peddie, Paul Riekert, Lloyd Ross, Nux Schwartz and Warrick Sony – spent time and resources turning Rigtingbefok into the special record that it is?

“I have no idea. You’ll have to ask them,” Herselman says with an incredulous shake of his head. “When I saw the final list of musicians and producers, I was freaked out. It’s insane, man. Why would all these ous do this? They didn’t get paid for it. This isn’t about money. But I guess a lot of people like the idea of a collective.”

That may be, I say, but you are the lynchpin.

“I [wish it more] for the songs, if I could say that,” he offers. “Though I don’t feel like they are entirely mine. It’s that Keith Richards thing. I don’t have to write the songs, I just have to be there when they arrive. I definitely have that feeling [about my songs]. Definitely.”

Herselman pauses and considers his next words.

“You know, I’ve never thought of myself as a musician – as being an artist and all that. I’m just an oke who plays the guitar. I love playing in bands because I love the conversation of music. I guess the album is made up of different people – mostly those that I’ve had stuff to do with through the years, and then there are others I’ve met only recently and even some I’ve never met. I met Sannie Fox in Kommetjie and we were just jamming, playing covers. She plays beautifully and has a lovely voice. She said: ‘You’re like a fucking jukebox.’ I was in a covers band at school. We played everyone – Santana, Chicago, Rolling Stones.”

But it’s Herselman’s original material that Fox and others tackle on Rigtingbefok. Sixteen songs culled from a treasure chest of some 70 demos that Herselman began sending out to friends over a year ago, in the hope that someone might want to do something with them. One of these was Michael Cross, who has been a friend and on-off creative collaborator for over 20 years, after turning up to film Die Kêrels’ last ever gig. Now Rigtingbefok‘s executive producer, Cross was the one who made the calls, sent the demos to potential collaborators, organised the sessions – relentlessly pushing the project forward over a seven-month period.

“Michael was the one who put it all together. He was able to send stuff out. I couldn’t do it. I still can’t. This is my office,” says Herselman, gesturing to his decidedly unSmart phone.

Now 56 (“I don’t know how, but here we go,” he says of his age), Herselman has not much more to his name than what fits into the room he lives in on Ampie Omo’s property and an old computer prone to viruses that keep corrupting his work. But there’s not a trace of self-pity when he describes his life now. You get the feeling that Herselman accepts this as the consequence of a lengthy heroin addiction that nearly killed him.

“Dead. People thought I was dead,” Herselman says of the years he became nothing more than a ghostly presence on the music scene, remembered for what he had done, not what he was doing.

He’s completely off heroin now and says he’s talking about it because he wants people to know that you can get off it. “When I was there in the thick of it, they said only five percent of people who get on heroin can get off it. But I did and I didn’t go to rehab. People can get off smack.” (Four days after Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death, Herselman reinforces this point when I get an email from Michael Cross that contains a message from Herselman. “There’s something called Suboxone (SA commercial name) that can help people get off smack,” he wants me to know.)

“I spent 25 years drinking. I spent 10 years on heroin. We went in through pethidine and morphine so there was two years of that as well. It’s a bizarre story, really. We got this free morphine and pethidine and we started shooting up for fun. I kind of remember thinking at the time, ‘it’s a finite amount, and it will be finished one of these days’. But half an hour after the last little ampoule was gone, I was at the Randburg Kentucky Fried Chicken buying smack. That was 10 years of my life.”

Why did you stop?

“I got tired of it. It’s like working at the SA Permanent (a South African bank). If you don’t dig it, you get the fuck out. Also, you run out of money – that’s great inspiration. And I had seen people almost overdose – friends, other people. You just know you have to get over it. It’s the same with drinking. I drank so heavily for so long. You go ‘what the fuck are you doing?’ The party’s over.”

These days, Herselman confines himself to beer, “because I know I can stop”.

“If I was drinking whisky now it would be another bottle, another bottle. I figured out a lot about myself coming off heroin. I didn’t go to rehab because I felt like then I would have lost. The rehab approach of all or nothing is hectic. That frightens me, that group hug stuff.

“But I didn’t do it totally on my own. I went to doctors who looked at me and said you are dead. Stop. People were amazing. Family supported me. I was lucky enough to have that. Not everyone does.”

Even though he disappeared from the public eye, Herselman managed to keep a modicum of normality going through his addiction.

“A lot of people didn’t know I was on it. Heroin is a weird drug. People have a funny idea that you are lying in the gutter and shit. It’s really not like that, you know. You can still function but I couldn’t get anything like a gig together. You can’t just suddenly go out of town. You can’t miss a day of smack. If you run out you are in shit. Getting off is a bitch. You get sick.”

But through it all, he kept writing because even though he writes in fits and starts – “I can write 20 songs in a month and then nothing for a year” – he finds his subject matter everywhere, in any circumstance.

“I can write a song about a parking meter” he says with a wry laugh. One of the songs on Rigtingbefok, “Shopping Mall”, “was just [about] going to the East Rand Shopping Mall and thinking ‘this is insane’. Songwriting is about transmitting an emotion. That’s what punk did. That’s what Die Antwoord do. And then someone says ‘yes, I feel like this’ and your song has connected.”

A lot of the material on the new album has been on the shelf for years – songs that didn’t fit whatever band he was in at the time, or during the GBB period when Kerkorrel’s songs were the primary material.

“We played those 14 songs for two years,” Herselman says now.

“That was the main frustration for me. I just had all these songs pouring out of me, but they were sitting on the shelf.” “Namakwaland”, for instance, was written for the first incarnation of Die Kêrels and Herselman says when he heard Francois Van Coke’s rasping, urgent vocals on the song he was “blown away”. “Sunday, The Morning” is another older song, written whilst walking home from Hillbrow Records Centre (where Herselman worked for many years) to his flat where he immediately set about recording the song.

“I still like that version, just me and an acoustic guitar and an old tape recorder,” he says, a trace of wistfulness in his voice. Die Lemme version sees Toast Coetzer joining Herselman on guitar and vocals, as well as Verashni Venkatasubramanian on sitar and Warrick Sony on bass, programming and production. The result conjures up the desolating, isolating thing that being strung out in the city brings. It’s just one of many inspired, unexpected recordings that are bringing Herselman’s material to life.

With each producer and the artists approaching Herselman’s material fresh, Rigtingbefok is unbounded by genres, exposing the rich sonic potential of his deep well of songs. Herselman admits that if he had made the album on his own, it would have come out very differently.

“I was in a state where I would have made this completely punk, freaked-out record. The old Kêrels vibe. I mean, I hadn’t made anything for 10 years. I’d just got off heroin. There was madness coming out of me. So I said to Mike: ‘Look I’m not in a place to make these decisions. Here are the songs. You decide on what to do.’”

The process of waiting to hear how his songs turned out in the hands of others was “both amazing and mad”. “There was never a band in the studio. Someone would come from Nelspruit and go to Durban and then to Cape Town before heading back to Johannesburg. With the Kêrels I was quite a bit of a Hitler in a sense. With both Ek Sê and Chrome Sweet Chrome, we played the songs live and got them very tight and then made each record in one day. We recorded the music and then Lloyd said go out and get drunk and get your throat messed up and come back and sing. No overdubs. Just that.”

Herselman has always loved playing live, and worries if he can take the songs on Rigtingbefok on the road. “Will I remember the words? My short-term memory is not great. I can walk into Checkers to buy a pie and come out with a Lottery ticket and a newspaper. The amazing thing is that my long-term memory is not bad. I was dronk a lot back then, but people can’t remember stuff that I can remember.

“I guess remembering the words will come with practice. Heroin also knocked my confidence big time. You know I have this thing about drugs. Whatever they give you, they will come and take away. But when they come to fetch it they will have robbed you as well. With heroin you feel that nothing can hurt you now and when it’s gone, you feel that everything is fucked. Everything.”

How do you get beyond that?

“Play the guitar. Play live. James Phillips said to me once: ‘How are you doing? Are you playing your guitar?’ I said: ‘I’m doing OK.’ He said: ‘If you don’t play your guitar you are going to get sick.’ I need to play more and write more. Heroin was isolating. You want to know where your next fix is. You don’t want to hang with people because they are going to find out what you are doing. Things like Facebook make you suddenly feel you are in touch again and you are able to start interacting with your environment.”

Actually, since Jannie van Tonder got him to sign up a while back, Herselman is very funny on Facebook. As a protest against the “terrifying headlines – you know, like ‘Three-year-old Survives Gang Rape’ “, he keeps up a regular stream of funny fake “headlines”: “Television Throws Man Out of the Window During Argument!” “Stork Requires e-tag To Deliver Baby!” “Long Leave, Politics! Long Leave!!”

Like the artists and producers who worked on Rigtingbefok, his re-immersion into day-to-day life is something of a revelation to Herselman.

“I was on the outs before all of this. I was kipping in the cemetery, in my mom’s car. I’d tell her I was going to use it to sleep at someone’s house but I would crash in the car. It was amazing. It was quite freeing in a way. Just walking through the night. Having nothing. It’s interesting walking through the streets at night. There is no-one about. I never encountered any shit. The only time I felt like now I might get into shit was when walking through Greenside and young, steroid whitey ous were around. But beyond that it was amazing. I’d kip at the Shell garage and the guys would say: ‘Are you OK, Madala? Can I get you some water? Play your guitar for me.’ Lovely – it was so nice to think that whole ‘darkie-whitey’ thing was [makes a twisting sound]. Now I was on the outs and they had the job, but they were checking on me. I walked out a lot of anger during that time.”

The idea of slipping out of society wasn’t entirely new to Herselman.

“When I was working at Hillbrow Records I thought if I had the guts I could go and be a hobo. I just never had the guts to do it. Maybe my time of walking the streets was a little dream that came true. But I was never totally on the outs – I know people (who could take me in). But I did transverse a little into that world.”

He’s slowly learning to receive the outpouring of affection that’s come his way with Die Lemme project, unimaginable when he was in the depths of his heroin addiction.

“This record is a lesson in gratitude essentially. Maybe I’m going to get knocked over and die now and this is it, but I felt embarrassed a lot, during the making of the album. I mean look at the ous who played on it, the producers who believed in me. They are great. Fuck. It’s easier for me to give than take. At one stage I said to myself: ‘Just relax and dig it,’ but it didn’t happen and I remain very humble and honoured. It sounds a bit like Oprah, but that’s what I feel.”

I leave you with this, dear reader.

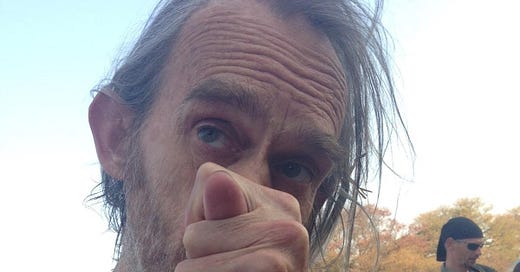

The photos of Gary Herselman that I have included here were taken - on 8 August 2014 - at Oppikoppi by Jay Savage, my partner in music adventures for the past 30 years.

For most of its 23 years the music festival blazed a trail, bringing together music and revelry in a brilliant, sometimes chaotic flourish on top of a hill in South Africa’s Limpopo province - “Oppikoppi” being an abbreviation of the Afrikaans “op die koppie” (on the hill).

That year the theme was Odyssey and, alongside a flush of homegrown artists (including, most memorably, an incendiary performance by aKING and a warm-hearted outing by The Hinds Brothers), we sat on the grass and watched Cat Power play. Her set was beset with sound problems but we were nonetheless glad she was there, the selection of the handful of international artists on the line-up of the three-day festival (in 2014 it also included Willy Mason, Editors, Sarah Blasko and Aloe Blacc) always coming straight out of the Oppikoppi team’s personal taste, one of the many things that made the festival as homely as a 20 000 capacity event can be. In an interview with a local newspaper during her visit, Chan Marshall revealed that, in spite of her stage name, she is a dog person. “In my past life I was a dog,” she confided. How could Cat Power have known that an artist who really believed himself to be a dog at one stage in his career, who, like her, had struggled with substance abuse, was also playing on that hill that year?

And also this.

You can listen to Rigtingbevok on Bandcamp here. For me, a standout track is “Doesn’t Make a Sound” with Arno Carstens, Chris Letcher, Albert Frost and Max Mikula but there’s plenty to love on the album. You can also watch Herselman with his band The Kêrels performing at the James Phillips Memorial Concert at the Bassline, Johannesburg in August 1995 (a story for another time). "Skin on Skin" contains one of the great Herselman lines in, “Outta shape is the shape I’m in.”

The only really detailed piece on Gary that I’ve read, so far. Lovely piece.

Lekker Diane. It's really good to read this again.