Living in Hell and Loving it

How my second Billboard article reminded me of the ephemerality of things

My first real job as a journalist after I left university was as an activist reporter for The Press Trust of South Africa, an alternative news agency in Durban. It was run by Marimuthu (Subry) Govender who was banned by the apartheid authorities and placed under house arrest and so only permitted to be in the office for a few hours a day.

Of course, I had worked before then, the combination of divorced parents, each with limited resources, meant my sister and I found ourselves starting our income earning lives at the coffee shop at the recently built Cabana Beach Hotel when we were about 12 and 13. It was managed by a woman named Hetty who twisted our ears when we did something wrong or that she didn’t like and not even the free milkshakes we were given as part of our pay could stop Catherine and I from sometimes leaving our shifts with tear-stained faces.

A postcard of Umhlanga Beach with Cabana Beach’s signature tiered hotel rooms in view

But Press Trust was my first full-time writing job and, in 1988, I’d report to the 12th floor of Salisbury Centre in West Street and get to work, calling my contacts at one of the many social justice organisations working in Natal for leads or writing up stories, like the one titled “Fifteen-year-old anti-apartheid girl activist on the run” - which I wrote with another journalist working at Press Trust, John Khuzwayo - that referenced a promise by then chief of the security police, Major General Basie Smit, to “crack down on youth leaders” or another on a street law project for children that included lessons on detention without trial.

What got me thinking about my time at Press Trust these past few weeks wasn’t ongoing - and seemingly unchanging - issues of social justice but, much more mundanely, the instrument that we used to get our stories out - to South newspaper in Cape Town, to New Nation in Joburg, to the Press Trust of India.

A key component of our small office was our teletype machine on which Angie (forgive me readers, I can’t remember her surname) would retype our already typed stories and send them into the world. This story on Poynter shows how this tech worked and asks if the “breaking news” ability of the teletype machine made it the Twitter of the 20th century. Except for that time when the security police raided our offices and confiscated our equipment and seized our funds, our machine operated less like an instrument of breaking news and more like the current ability of social media to get news out during periods of state repression and suppression.

If you’re wondering how this all relates to the primary concern of Notations - the joy that music and other things bring - then let me explain. I recently came across a fax that was sent to me on 06 May 1997 at precisely 12h20 from Christine Chinetti. The cover page read, “Dear Diane, Just in case you haven’t seen it, your name in Billboard - Congratulations! Article number 2. Isn’t that great?”

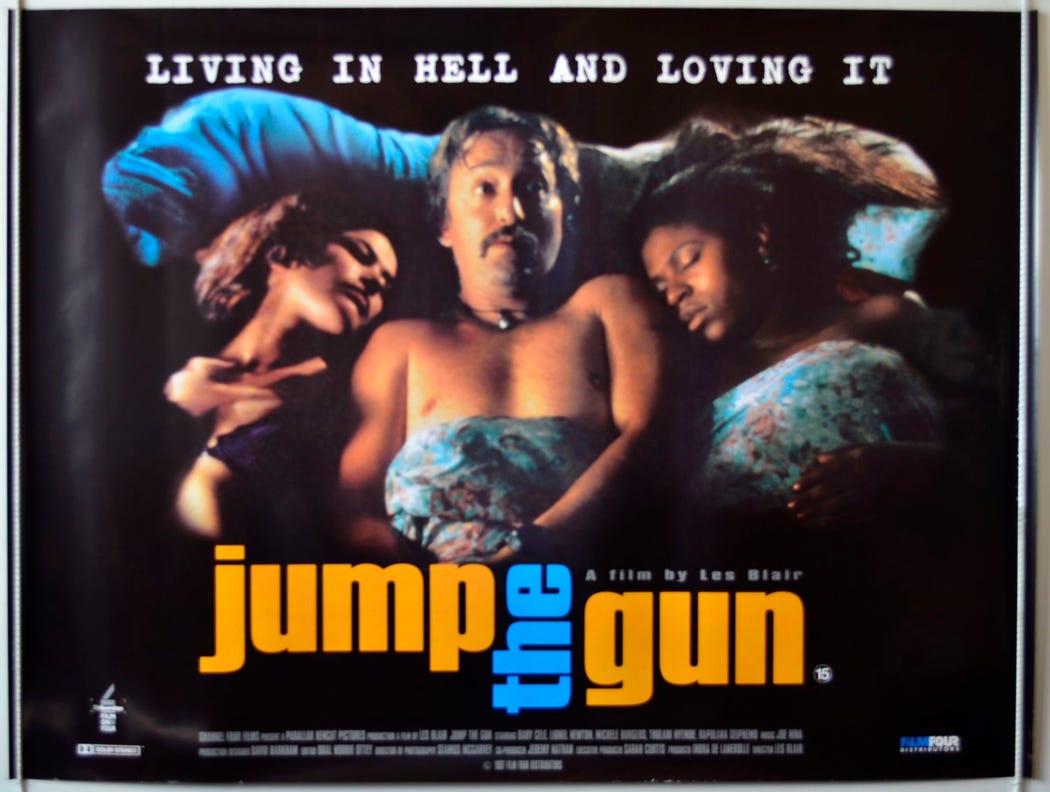

It was great - and Christine, Billboard’s European Sales & Marketing Director and a lovely human being, was instrumental in me becoming the South African correspondent for Billboard Magazine for more than a decade. I can’t remember what my first article was about but the second one, photocopied and faxed from London, appeared as the last entry in a global round-up column. It reported on the soundtrack album that accompanied the Les Blair-directed film, Jump The Gun, which was, I boldly asserted at the start, “one of the most significant movies to emerge from post-apartheid South Africa”. The short piece continued,

“Released May 28 here, the film unravels the schizophrenic nature of contemporary Johannesburg and features Joe Nina, one of the country’s youngest and most prolific songwriters/artists/producers in an important acting role. Nina (real name Henry Xaba) composed the film’s score and contributes three original songs to the soundtrack compilation to be released May 2. ‘To be able to write music that connects so directly with my life, without regard to whether or not it will be a huge hit or sell thousands, has opened up a whole new dimension for me,’ Nina confides. The remainder of the compilation is made up of tracks from artists not traditionally associated with one another. Among them are M’du and Mashamplani who, along with Nina, are at the forefront of the current kwaito (black dance) explosion … ‘In terms of musical styles, this album is a first for this country,’ says Jay Savage, executive producer of the album. ‘But, while there is a great variety of sounds, there is a unity and universality in the concerns of the artists that, like the movie itself, make for a gritty and very contemporary portrayal of post-apartheid South Africa.’

In some ways my second article for the American music publication had come easy. Jay Savage was - and still is - my partner and Jump The Gun’s producer, Jeremy Nathan, was - and still is - our close friend. This meant that I’d had an up close view of the selection of songs and musicians for a film that came with the still memorable tagline “Living in hell and loving it”. But, a trio of years after South Africa’s first democratic elections, it was unusual to find artists working in different genres on one soundtrack - or any platform - and that made the album notable. Mandoza was still three years off from releasing “Nkalakatha”, which became the one - and, a little tragically, still probably the only - kwaito anthem known to white South Africans and the fuzzing over of the boundaries of genre, exemplified by an act like Beatenberg or Bongeziwe Mabandla, were a long way off.

I’ve looked but can’t find any official traces of Jump The Gun, the movie or the soundtrack, on the many streaming services around. It exists somewhere on a reel, on a video tape, on a CD but has not yet made it out from under a pile of archival content onto current streaming services, at least as far as I can tell. I wish it would resurface. It was a funny, moving film with a great soundtrack (and a cameo appearance by Jay that I’d love our children to see). You can read Variety’s review of it here and I agree: Lionel Newton’s performance is memorable, Baby Cele brings the heart and the late casting director Moonyeenn Lee is key to the ensemble cast.

“As the bemused Clint, who perpetually looks as if he’s wandered into the wrong party, Newton is superb, balancing the contradictory emotions of an Afrikaaner, who finds the rules suddenly changed, with warmth and self-irony.” Variety review of Jump The Gun.

The schizophrenic nature of Johannesburg that I wrote about 25 years ago still defines the city but the fax that Christine so thoughtfully sent me in 1997 is not sticking around (even though, at least according to this article, fax machines are still being used) because the thermal paper that was neatly rolled up in our fax machine in our Orange Grove home is built to fade. To be able to properly read what Christine fed into the Billboard fax machine I had to take a photo of the page on my phone and enlarge the faded bits. New technology giving the past a helping hand.

So this piece is really about the ephemerality of things.

Of the obsolete telefax machine transmitting vital news of the anti-apartheid struggle from a South African port city to the world in 1988.

Of the fax messages, sending records of benchmark career moments that fade and disappear.

Of the movies made and celebrated and loved and now forgotten.

Of the musicians who helped create music to soundtrack a longed-for freedom, now, like Tokollo “Magesh” Tshabalala, gone from the world.

Of memories that are moving past the point of retrieval.

I leave you with this, dear reader.

In the absence of the Jump The Gun soundtrack being easily available, here are a selection of songs by some of the artists featured on it, including Joe Nina, a wholly underrated member of the kwaito revolution and a gifted all rounder.

Listen to:

Joe Nina’s “Maria Podesta (Ding Dong)” and “S’bali”.

Mashamplani’s “Hey Kop”, featuring the late kwaito icon, Tokollo “Magesh” Tshabalala.

Bright Blue’s “Weeping”, here accompanied by the original video, shot by Nic Hofmeyr during the state of emergency and featuring a moving shot of the late Basil “Manenberg” Coetzee on sax, filmed in Manenberg township.

Jump the Gun! Now that has memories flooding back, cloudy as they are decades later. Nice Di!